Albert B. Fernandez

Lecture read at the New Buffalo, Michigan, community library, May 9,2023

I

Deconstruction. You’ve probably heard the word, before this talk. The originator of deconstruction, a French intellectual named Jacques Derrida, who died in 2004, has been called “The world’s most famous philosopher,” an appellation that was corrected to “The world’s only famous philosopher.” In spite of the abstruse, uber-academic character of Deconstruction, the word at least, has already appeared on the entertainment scene. There was a tv movie called Deconstructing Sarah back in 1994, and in 1997 Woody Allen came out with Deconstructing Harry. In that movie the professor played by Allen mentions a student paper entitled “Oral Sex in the Age of Deconstruction.” The implication is that Deconstruction is something outrageous, farfetched, postmodernist, and this is not a misleading implication.

One also comes across the term in the press and the tv pundit shows. Typically the writer or speaker uses the word with ironic awareness that deconstruction is a fancy and fashionable academic word and that maybe nobody really knows what it means, but all the same it is used, in the sense of a thorough criticism, especially a criticism that picks apart an implicit line of thought. And again, these echoes of deconstruction are not misleading. The very word, “de-construction,” conveys a pulling apart and pulling down. When I was at Cornell University, a hotbed of Deconstruction at the time, its practitioners were colloquially referred to as “The Wrecking Crew.”

Popular culture has been picking up the shockwaves of something that began to happen in Paris (naturally) in the mid-1960’s, and caught on like fire in American academia, more than in Europe, especially at Yale University, where a group of faculty followers of Derrida—Paul DeMan, J. Hillis Miller, Geoffrey Hartmann, and Harold Bloom–picked up the title of “The Yale Fab Four.” How shocking the advent of Deconstruction was elsewhere you may gather from a collective statement, circulated in 1992 by a group of 18 Philosophers at Cambridge University, condemning Derrida for “denying the distinctions between fact and fiction, observation and imagination, evidence and prejudice.” Michel Foucault, a classmate of Derrida, who has a reputation among historians comparable to Derrida’s among philosophers, once called Derrida an “intellectual terrorist,” much like the kettle called the pot.

Jacques Derrida, born in Algeria, studied in Paris, at the Ecole Normal Superieur, which is kind of a French all-expenses-paid think tank for advanced academics and intellectuals. Derrida’s most influential works are, in chronological order, as follows. “Structure, Sign & Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences,” meaning sciences like sociology and psychology, was a long lecture he delivered at Johns Hopkins University, and which turned out to be the beachhead for the French invasion of American academia. The second of these influential works is Of Grammatology –“grammatology” means the study of writing or, more narrowly, the study of inscriptions or markings (“gramma” in Greek); and finally, “Differance,” also originally delivered as a lecture, so that nobody could tell that the title was misspelled (more on this later). These three titles all originally appeared between 1967 and 1968, having been written in a kind of fit of philosophy.

All of Derrida’s books and essays are difficult reading, but if after this talk you want to learn more about Deconstruction, I’ve cited “Semiology and Grammatology” in the handout. “Semiology & Grammatology” is an interview with Derrida, one of three in a book titled Positions. It’s short, and it’s relatively easy reading.

But generally, the writing of Deconstructionists is notoriously sybillline. What do you get when you cross a Deconstructionist with a member of the Mafia? You get an offer you can’t understand. Here’s a typical Deconstructionist passage, from Derrida’s Of Grammatology:

The metaphor of translation as the transcription of an original text would separate force and extension, maintaining the simple exteriority of the translated and the translating. This very exteriority, the static and topological bias of the metaphor, would assure the transparency of a neutral translation, of a phoronomic and nonmetabolic process. Freud emphasizes that psychic writing does not lend itself to translation because it is a single energetic system (however differentiated it may be).

Not surprisingly, deconstructionists regard qualities such as “clarity” and “simplicity” with suspicion and disdain. Indeed, one way the whole message of deconstruction could be summed up is as the claim that up to the present philosophers have been oversimplifying. This presentation is therefore an unauthorized attempt to translate deconstructionist thought into relatively plain language, which Derrida calls “a conceptuality adhering to classical strictures.”

II

Very basically, Deconstruction is two things: 1) a way of analyzing philosophical and literary texts and 2) a philosophy, a philosophy that claims that there is no final, uncontestable interpretation of any text and that, at its most radical, extends the claim to apply not just to texts but to everything. Deconstruction thus asserts that reality cannot ultimately be resolved–“resolved” in the optical sense of making things clear and distinct. And Deconstruction is indeed like the humanities version of quantum physics, which similarly holds that the characteristics of subatomic particles cannot be fully resolved.

So, Deconstruction is, first, a way of reading and critiquing texts, especially philosophical and literary texts, by looking for implicit meanings that contradict the ostensible point of the work. Deconstructionists look for what they call “aporias,” a Greek term that can be translated as “impasse” or “tight spot,” places where writers unwittingly undermine or call into question their own arguments and purposes. As Jack Reynolds of LaTrobe University explains: “Deconstruction contends that in any text, there are inevitably points of equivocation and ‘undecidability’ that betray any stable meaning that an author might seek to impose.” The deconstructionist fills in what the aporia suggests and provides one or more counter-versions of the work in question. This kind of interpreting is often called “reading against the grain,” or “double reading.” The procedure I have just described is not really new. You may have heard, for example, William Blake’s remark about Milton’s Paradise Lost that “Milton was secretly of the Devil’s party,” because Satan comes out looking more heroic than any of the other personages in Milton’s epic. What Milton claims is the purpose of Paradise Lost, “to justify God’s ways to man,” in his own words, is undermined by Milton’s portrayal of Satan.

III

I’ll provide two examples of deconstruction carried out by Derrida. Before Derrida published his work, one of the most authoritative schools of European philosophy was what is called “phenomenology.” The name comes from the Greek “phenomenon,” meaning “that which shows itself.” Phenomenology was founded early in the nineteenth century by the German philosopher Hegel, and the key idea was that the best way to understand something is to . . . shut up mentally, to clear the mind of all preconceptions and expectations. The American poet Wallace Stevens unintentionally spoke for phenomenology when he wrote:

Let’s see the very thing and nothing else

Let’s see it with the hottest fire of sight.

Burn everything not part of it to ash.

—Credences of Summer

The leading exponents of phenomenology in 20th-century Europe were the philosophers Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger, and the former, Husserl, was the target of one of Derrida’s most important deconstructions, which appeared in D’s first full-length book, Voice and Phenomenon. One of Husserl’s major theses was that truth is found in what he called “The Living Present.” It’s Husserl’s term for the quintessential now, the present moment. It’s in that instant of the present before it’s carried away into the past where reality is encountered and understood most clearly and without clutter, according to Husserl. The living present, as Husserl explains it, is within human time, meaning time as experienced by humans, not as measured by clocks. The living present is caught between the immediate past, the short-term memory, which Husserl called “retention,” and anticipation of the immediate future which he called “protention.” Derrida, who has often insisted that texts deconstruct themselves, commented that “phenomenology appears to us to be tormented if not contested, from the inside, by means of its own descriptions of the movement of temporalization” –temporalization is another term for what has also been called “human time.”

Derrida seizes on Husserl’s three-part division of human time and claims that Husserl’s “living present” does not exist. The present cannot be isolated as something that’s sandwiched between retention and protention, rather, in human time, according to Derrida, past, present, and future are indistinguishable and all three seamlessly contaminate all three. Here’s the future coming, oh wait, it’s already present, oops, it’s gone, I’m just remembering it. The cherished moment of greatest clarity, of unsullied presence, does not exist. For Derrida, human time, like human language, and human existence, offers no clarity.

Another of Husserl’s principal teachings is that it is possible to understand oneself by means of interior monologue, to which he attributes a privileged revelatory status like that of the “living present.” And when we talk to ourselves in dialogal form, Husserl says, we are merely pretending that we are in conversation with another party. That is no pretense, says Derrida, in Voice and Phenomenon. He points out that humans think with a voice, even when they are alone and physically silent, so that the interior monologue immediately unfolds into one who speaks and one who listens, without ceasing to constitute a single person. “The voice hears itself,” as Derrida puts it (Cisney 150). The multiplicity of human personality, previously recognized by Freud and by Hegel, rules out the phenomenological idea that we can be transparent to ourselves. There’s more than one of us at all times.

Neither the “living present” nor the interior monologue, as Husserl constructs them, are real according to Derrida.

IV

A second classic Derridean deconstruction—if the adjective “classic” can be applied to anything produced by Derrida–is his critique of the linguistics of Ferdinand de Saussure, who is known as “the father of linguistics.” Saussure’s main claim in his Course in General Linguistics, which came out in 1916, is that language should not be thought of as a collection of independent values, that is, as a collection of words each of which has a meaning of its own. Rather, Saussure continues, language is better understood as a system, in which each term or word or phrase carries meaning because of its difference from all other words in the system, and not because of any intrinsic characteristic. Saussure provides the example of chess pieces as a signifying system. Although chess pieces do tend to have traditional features—the king with a little crown on top, for instance—their identity ultimately derives from their relation to the rest of the playing pieces. You can use anything as the chess pieces—rocks–as long as you can distinguish the king from the bishop and the bishop from the knight, etc. The colors . . . can be anything you want as long as you can tell the pieces of one player from those of the other. And so it is, according to Saussure, with language. The reason why “hat” can work fine to designate what it designates while “chapeau” works equally well to designate the same thing in another language is because both words, as well other words in other languages, get their meaning, their “value” as Saussure calls it, from fitting into the spot in the system that corresponds to what we call a hat. In other words, the relation of words in a language and of signs in a signifying system to what they designate is, as Saussure famously said, arbitrary. We, in this room, could arbitrarily agree to call the podium “XYZ,” and among us it would work as well as calling it “podium.”

Derrida thinks that Saussure doesn’t go far enough. If the terms in a signifying system are arbitrarily chosen, what about the signifieds, the concepts that the signifiers in the system stand for? Are those arbitrary? Or required by reality? Long ago, Plato, in a little-known dialog called The Cratylus, declared that “language instructs us in the division of the world.” In other words, reality is pre-divided in a certain way and language simply reflects that division. Or is it we, in our languages, who decide how reality is to be parceled out? Do all languages divide it the same way? Do all species?

Saussure does not say that consciousness prior to language is already divided into identities. He says that without language consciousness is just a mess. But, as Derrida points out, that’s begging the question, the question of how that original mess gets transformed into signifying systems, into languages.

It could be said that in these two deconstructions, of Husserl and Saussure, Derrida is reiterating what Friedrich Nietzsche formulated a century before him with one of his epigrams: “There are no facts, only interpretations.” That’s not the same as saying that there are no truths or that there is no reality, as Derrida is sometimes charged with believing. The very act of discoursing and writing rules that out. You can’t say “it is true that there is no truth.” Rather, if you take Nietzsche’s epigram, which is itself open to interpretation, as meaning that you cannot make a valid truth claim without interpretation of raw data, that message is shared by the deconstructionists. Nothing is a complete phenomenon, nothing fully & obviously shows itself –in Derridean language, nothing is fully present. The present itself is ragged and mixed up with past and future. We cannot identify or know anything without associating it with other things, like the chess piece in Saussure’s example, like any utterance in a language.

V

And yet the mainstream of philosophy has pursued, in Derrida’s words, “the determination of being as presence.” In Deconstructive thought, “presence” means that which can stand by itself, and be understood by itself. The philosophical tradition has taken as its points of departure what it has naively considered self-evident, fully present, right in front of you, needing no explanation, independent of origin, history, or context. That describes the typical points of departure of various philosophies—for example: Being, the self, God, the good, Truth, nature, spirit, the living present.

As a counter to this philosophical tradition, Derrida did more than deconstruct particular works. He laid out a core philosophy–although he would no doubt object to my deploying that phrase—especially in the text titled DifferAnce.

For Derrida & deconstructionists the meaning of what is said and written is not stable, because the context is always changing, the language is always changing, the present is always slipping away. As I speak, even now, what I mean will not be exactly what you think I mean. Indeed, what I mean now with these words is not exactly what I meant when I went over these same words a few hours ago. All signs refer to more than one thing. Words and statements are nodes of possible significations. All ideas connect with other ideas, and those ideas in turn lead to others, which may be contradictory, sooner or later are contradictory. Anything that is said can be unsaid. There is an infinity of meanings, like the infinite library in a short story by Borges that you may be familiar with. Derrida’s word for the boundless galaxy of meanings is “The text.” A text is a network of ideas that has no boundaries: you can go on and on interpreting, finding connections. But Derrida doesn’t say “a text,” he says, in what may be his most famous claim, “Il n’y a pas dehors texte,” “There is nothing outside the text.” The text is the world. Everything can be interpreted, in relation to an endless series of possible contexts. Everything is like a sign; everything is a sign.

Mainstream philosophy, as noted earlier, has long been engaged in what Derrida calls “the metaphysics of presence.” And we too take it for granted that we inhabit a universe of presences—presences in any sense of the word, a series of nows, of living presents, of things and people about which you can say “It is what it is” as if that was all there is to it. In Derrida’s own terms, presence is that which is “manifest, that which can be shown,” which is the meaning of the Greek word “phenomenon.”

Signification is the opposite of presence. The sign always marks an absence, points to something that is not there. And, from the standpoint of Derrida and Deconstruction, we would be closer to reality if we saw ourselves inhabiting not a universe of presences, but a universe of signs.

Deconstruction is a new vision not only of writing, but also a new vision of reality as a boundless tangle of interconnected signs. If you take just one thing home from this talk, it could well be what I have just said: Deconstruction is a new vision not only of writing, but also a new vision of reality as a boundless tangle of interconnected signs.

In his Course on General Linguistics, Saussure declared “Everything that has been said so far boils down to this: in language there are only differences . . .differences without positive terms.” What goes along with the affirmation of the sign is the affirmation of difference, as distinct from philosophies, like Heidegger’s, centered on capital-b Being encompassing lower case “beings” plural, or other philosophies departing from foundational presences such as listed earlier. Derrida’s most general and philosophical work is DifferAnce. Differance spelled with an A—differAAnce, a multiple word-play that mainly indicates that difference is not an attribute of things but an ongoing process. Derrida has the audacity to say that differAnce is “older than being,” that is to say, comes first, before being. We are used to thinking of difference as something that emerges between beings. We say, here is podium and here is a microphone, and there is a difference between them. But if Derrida is right about the implications of Saussure’s thought, we would not be able to identify the podium and the microphone if we did not start by distinguishing between them, and between them and other items around us. Even at the level of sheer perception and how the visual cortex works, everything we see has to be perceived as not something else and not anything else. In terms of perceptual psychology, any object of sight has to be foregrounded, delineated to be recognized. “DifferAnce,” Derrida says, is the process that “makes possible the presentation of the present.” DifferAnce with an A is what causes the endless play of differences with an “e”. “DifferAnce,” according to Derrida, “would designate a constitutive, productive, and originary causality, the process of scission and division that would produce or constitute different things or differences.” I repeat “produce different things.” Thus diffferance comes first, is “older than being.”

Mainstream philosophy, as noted earlier, has long been engaged in what Derrida calls “the metaphysics of presence.” And we too take it for granted that we inhabit a universe of presences—presences in any sense of the word, a series of nows, of living presents, of things and people about which you can say “It is what it is” as if that was all there is to it. In Derrida’s own terms, presence is that which is “manifest, that which can be shown,” which is the meaning of the Greek word “phenomenon.”

Signification is the opposite of presence. The sign always marks an absence, points to something that is not there. And, from the standpoint of Derrida and Deconstruction, we would be closer to reality if we saw ourselves inhabiting not a universe of presences, but a universe of signs.

Deconstruction is a new vision not only of writing, but also a new vision of reality as a boundless tangle of interconnected signs. If you take just one thing home from this talk, it could well be what I have just said: Deconstruction is a new vision not only of writing, but also a new vision of reality as a boundless tangle of interconnected signs.

In his Course on General Linguistics, Saussure declared “Everything that has been said so far boils down to this: in language there are only differences . . .differences without positive terms.” What goes along with the affirmation of the sign is the affirmation of difference, as distinct from philosophies, like Heidegger’s, centered on capital-b Being encompassing lower case “beings” plural, or other philosophies departing from foundational presences such as listed earlier. Derrida’s most general and philosophical work is DifferAnce. Differance spelled with an A—differAnce, a multiple word-play that mainly indicates that difference is not an attribute of things but an ongoing process. Derrida has the audacity to say that differAnce is “older than being,” that is to say, comes first, before being. We are used to thinking of difference as something that emerges between beings. We say, here is podium and here is a microphone, and there is a difference between them. But if Derrida is right about the implications of Saussure’s thought, we would not be able to identify the podium and the microphone if we did not start by distinguishing between them, and between them and other items around us. Even at the level of sheer perception and how the visual cortex works, everything we see has to be perceived as not something else and not anything else. In terms of perceptual psychology, any object of sight has to be foregrounded, delineated to be recognized. “DifferAnce,” Derrida says, is the process that “makes possible the presentation of the present.” DifferAnce with an A is what causes the endless play of differences with an “e”. “DifferAnce,” according to Derrida, “would designate a constitutive, productive, and originary causality, the process of scission and division that would produce or constitute different things or differences.” I repeat “produce different things.” Thus diffferance comes first, is “older than being.”

DifferAnce is the key concept in deconstructionist philosophy, and it’s easier to wrap your mind around it if you think of the process of differance as happening only in the mind, as the constant play of associations and distinctions. But for Derrida differAnce, the play of differences, is what animates the world itself. With his writings on difference Derrida makes himself the heir of the subordinated tradition of philosophy in Western thought, not the philosophy of presence, but the philosophy of Heraclitus who, before Socrates, declared: “You never gaze into the same fire. You never step into the same river.”

VI

After all this we might say, ok, so, contrary to what we assume on a daily basis, to say nothing of what our forefathers may have believed, things are very unstable and uncertain, so what are we supposed to do about it, give up on understanding anything? Derrida and Deconstruction are very much a part of a major cultural current of modernity. From the perspective of cultural history, Deconstruction is a radicalization, a further radicalization, of Modernity’s assault on certainty. After centuries of attempting to demonstrate the existence of God and subsequently the existence of other entities, Western culture, began in the latter nineteenth century to assert by implication or directly what Paul of Tarsus had said to the Corinthians before the demonstrations of Aquinas and Augustine, that we see “but through a glass, darkly.” Here for example is Joseph Conrad writing at the end of the nineteenth century, and anticipating what the Deconstructionists will say nearly verbatim:

The only indisputable fact of life is our ignorance. Besides this. There is nothing evident, nothing absolute, nothing uncontradicted; There is no principle, no instinct, no impulse that can stand Alone at the beginning of things and look confidently to the end.

And there are those famous lines by T.S. Eliot:

What are the roots that clutch, what branches grow

Out of this stony rubbish? Son of Man,

You cannot know, or guess, for you know only

A heap of broken images.

“A heap of broken images.” Even the sciences, after the advent of quantum physics, could no longer lay claim to the assurance that Isaac Newton had flaunted (“I make no hypotheses, he had said). And here’s F. Scott Fitzgerald, writing after the First World War that “all faiths in God shaken; all faiths in man broken.”

And yet, Derrida himself, Derrida the man, was not as thoroughly skeptical as his writings might lead one to believe. When he came to a seminar at the University of Chicago, some of us in the seminar, partly because Derrida gives very few interviews and doesn’t want his picture taken, half-expected him to look like Merlin the Magician, all in black, with an owl on his shoulder, feet hovering above the floor. As it turned out, although he was dressed all in black, Derrida would actually say human-type things, like, “Where’s the restroom?” And he wouldn’t deconstruct your answer, and would, apparently, find the restroom. When he was growing up, he wanted to be a professional soccer player. He likes American hamburgers (as opposed to French hamburgers).

If Derrida is such a regular guy and carries on so normally, what then is this man really opposing? And what’s the point of all this Modernist and Post-Modernist skepticism? Judging from Derrida’s own behavior at the University of Chicago, he’s not out to deconstruct us out of talking to each other. His target is not the simple, everyday belief that things are to some extent predictable and understandable, which even radical philosophers need to have to get on in the world. Rather than attacking what is called “common sense,” at least part of the effect, if not necessarily the conscious purpose, of the Modernist, Post-Modernist, and Deconstructionist culture of uncertainty is to undermine fanaticism and arrogance, which tend to go along with certainty. With what success, this undermining, in the 20th and 21st centuries, is, to say the least, debatable. From this perspective, the Twentieth century assault on certainty, right up to Derrida, was a reaction to the jingoism that prevailed in the years leading up to the First World War and subsequently. On the other hand, it can also be said that the effect of Modernist culture and of work as profoundly iconoclastic as Deconstruction is to promote lack of commitment, to enlarge the ranks of the cynical, to foster the detached, indifferent intellectual, the “wishy-washy liberal.” As William Butler Yeats wrote,

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

—The Second Coming

In line with Yeats’ criticism of the century, contemporary writers such as Wayne Booth and George Steiner, in his pointedly titled Real Presences, have responded to Derrida by proposing that readers just have to make up their minds about what a writer means, not because it is possible to determine that meaning beyond doubt, but because we are obligated to at least try to understand those who address us. This criticism of Deconstruction concedes that it may be philosophically and intellectually right, but repudiates it on ethical grounds. We must simply try our best to understand each other.

VII

The Friends of the New Buffalo Library series announcement for this presentation says that “an extended example of deconstruction will be included time permitting.” I think that the time that remains permits the following not so extended example of deconstruction, which I have used in my classes.

I said earlier, apropos of William Blake’s comment about Milton’s Paradise Lost, that deconstructive moves, such as double reading, are not as novel as one might suppose. But the critiques authored by deconstructionists are groundbreaking in comparison with the mainstream of Twentieth Century Anglo-American criticism, and what was once called the “New Criticism.” The New Criticism held it as an article of faith that great literary works are above incoherence, that they are, to use the metaphor of Cleanth Brooks, “well-wrought urns” in which every little detail fits, crystal artifacts of perfect form wherein every line, every comma contributes to a unified effect. For Deconstruction, on the contrary, a work of literature or art is a field of conflicting forces of meaning, as one deconstructionist put it.

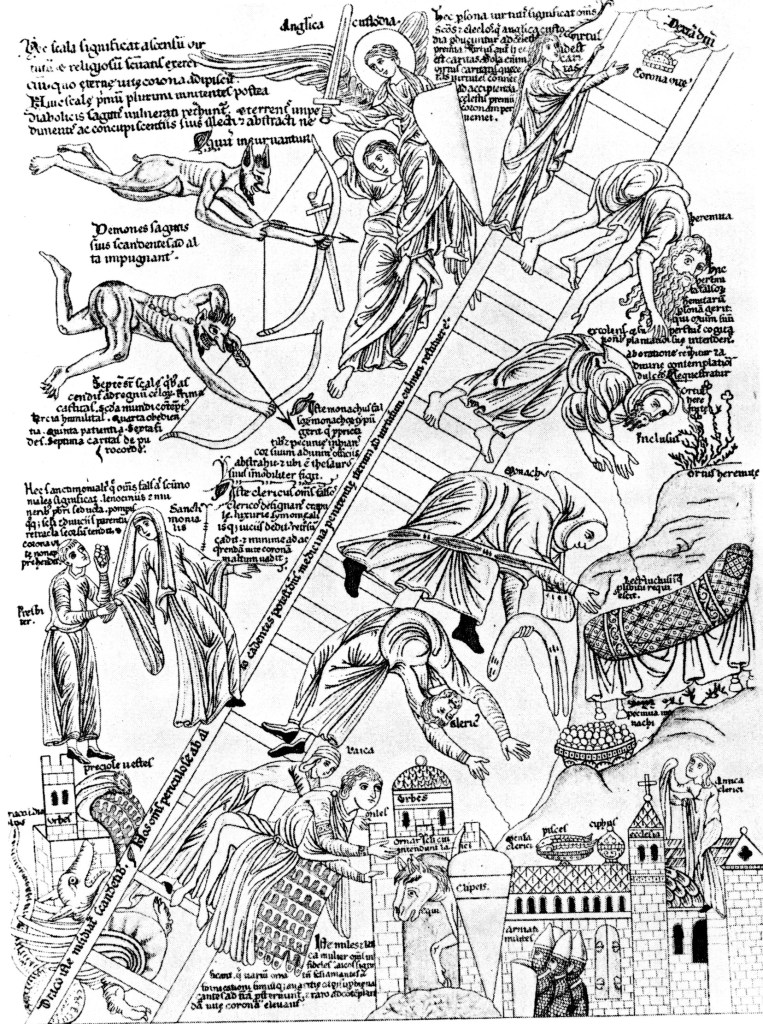

The world, the flesh, the devil . . . . You are looking at an illustration from an eleventh century manuscript showing Christians on a ladder to Heaven. Demons try to intercept them, angels defend them, and temptations cause them to fall off the straight and narrow: temptations to avarice, to sloth, to gluttony, and to the things that the wicked cities have to offer. One christian, who appears to be a monk, has committed the fatal error of leaning out to smell or pick a flower. In christian lit, going as far back as the writing of Thomas Aquinas–and later the doctrines of the Council of Trent and the Book of Common Prayer– the enemies of the soul were identified as the world, the flesh, and the devil.

But starting in the fourteenth century there was, as is well known, a Re-naissance or re-birth of interest in classical Rome and Greece, in the works of the pagans, and there arose a neo-pagan culture that came to be called “Humanism.” Humanism celebrated, among other things, the human body and brought a new appreciation of the beauty of nature. Appreciation of the beauty of nature comes easily to us, but in those days it was something subversive and dangerous that could easily be sinful. The Renaissance poet Petrarch, who as far as is known was the first European to climb a mountain without having to, after reaching the summit of Mount Ventoux in the Alps and marveling at the view, was overcome by religious guilt, and he read a passage from Paul the Apostle admonishing Christians against admiring nature and forgetting their souls. Petrarch himself writes: “I closed the book, angry with myself that I should still be admiring earthly things.” As late as the 16th century, the painter Paolo Veronese was summoned by the Inquisition to justify his insertion of pagan elements in his painting of the last supper. The following is taken from the transcript of the inquisition of Veronese:

Does it seem suitable to you, in the last supper of Our Lord,

to represent buffoons, drunken Germans, dwarfs, and other such absurdities?

VIII

Here is a painting of a common subject in Christian iconography, the baptism of Christ, painted by Giotto di Bombone circa 1305. A common motif, not only among christians but among the many religions that prescribe worship of a supreme sky god, is this vertical construction: The God directly above the hero, in this case a redeemer hero, receiving the beneficent rays of the sky god. Giotto painted this scene before the Renaissance and before even the earliest development of the art of perspective. And you can see that behind the baptism . . . there is no depth, only a blue wall, almost as if the earth did not exist. Compare with the following:

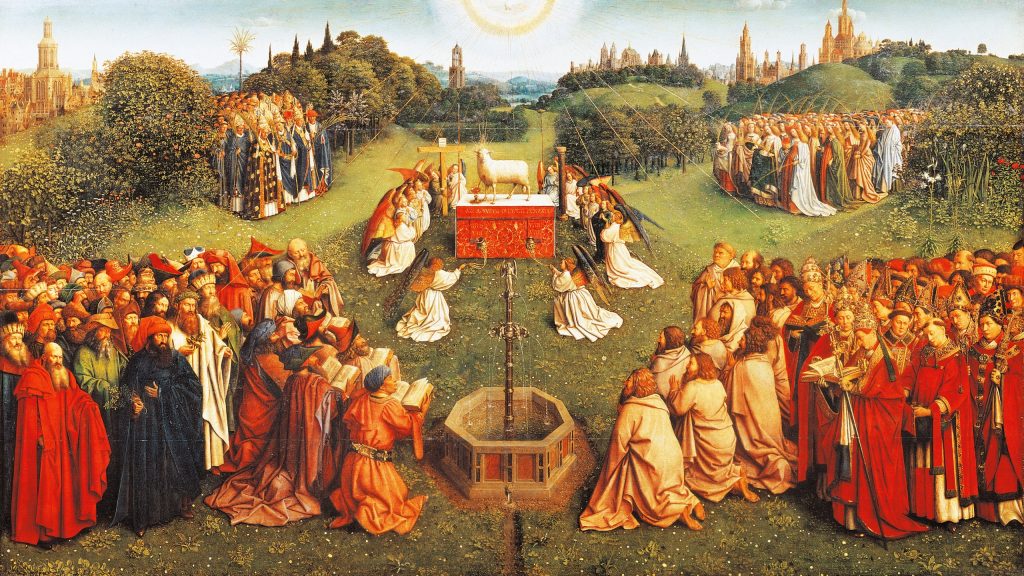

Now you’re looking at a painting created in the early Renaissance, by the Flemish brothers Hubert and Jan Van Eyck, six hundred years before today, circa 1425. This painting, The Adoration of the Lamb, which is the central panel of an altarpiece for the cathedral of the city of Ghent in Flanders.is often called the first modern landscape, or even the first landscape.

Is this a coherent work of art, or a field of conflicting meaning? Is it an adoration of the Christian lamb, representing Christ, or is it a scene of nature worship?

Surely the brothers Van Eyck were attempting something that would be both, that would harmonize the tension between Christian piety and the new humanism. And they attempt this by populating a beautiful landscape not only with the universal congregation of the blessed, which includes Church fathers and noble knights, as well as women martyrs, but also classical philosophers [this is supposed to be the Roman poet Virgil]. Furthermore, the Van Eycks have centered the painting on an elaborate and extended pictorial metaphor of communion between this world and Heaven. The contents of the painting are arranged around a vertical axis, an axis that connects God in Heaven with the soil of the Earth. At the top and center of the painting, God, in the form of the Holy Spirit, the second person of the Trinity, sheds his grace, represented by rays of light, far and wide. But directly illuminated by the divine rays is the Lamb, God’s gift of His own son as sacrificial redeemer. The sacrificial lamb’s blood then flows into a chalice. And directly beneath the altar, the Fountain of Life flows out to the earth. All of it along the line of a central, vertical axis, along which God’s grace flows down to earth.

If we examine this text, this pictorial text, from the standpoint of deconstruction, we look for something within the text itself that undermines its ostensible message of communion between this world and heaven.. We look for what in the vocabulary of deconstruction is called an aporia, which, as I said before, is an originally Greek word meaning tight spot, impasse, crisis. And this aporia, this location where the text begins to unravel. . . is here [pointing to center of horizon in the painting]. Wither the eye of the viewer from here?

Does it continue toward God, or does it turn to this world? Here the viewer has a choice between continuing to follow the vertical axis, or breaking off at a right angle to the vertical and looking toward the horizon. Here the vertical axis loses its hold on the viewer, who like a christian falling off the ladder of virtue, wanders into the horizontal, looks toward this hazy distant horizon, a distant hazy horizon which, after this painting, became a recurring feature of landscape art. Viewers may imagine flying toward the horizon, or past it, toward other regions. At this point, this point of aporia, the adoration of the lamb has turned into a dream of domination of the earth. The horizon disrupts the vertical attention to God and the cosmology that goes with it.

You could say: well, the effects you’ve been calling attention to, and what you regard as a deviation from God and piety, is simply the result of a painter practicing the state of the art in his time. Yes, these effects and the disruption they produce are made possible by a mastery of the art of perspective that was beyond the power of Giotto in his baptism of Christ. But the art of perspective discovered during the Renaissance was itself a turning away from piety with new interest in what is seen in this world. It’s not a mere coincidence that the development of perspective and of landscape art was soon followed by the great age of European exploration of the earth.

Well-wrought urn in which everything fits to convey a meaning, or field of conflicting forces of meaning? From the traditional standpoint the Van Eycks’ Adoration of the Lamb affirms the communion of the blessed on Earth with God, conveyed by the pictorial means of a double movement of adoration from below and grace from above, against the backdrop of nature. The deconstruction of this work of art that I have attempted shows the way in which nature within the painting is not a mere backdrop but also a temptation to turn away from God in heaven and toward the things of this world, the things which the humanist civilization of the Renaissance was to increasingly value as it led the way to modern times.

(c) Albert B. Fernandez

Comment space is below the buttons